Snowshoeing in Avalanche Country: Crucial Information

Avalanche Safety

Anywhere in the mountains where there is a pitch of 25 degrees or more, there is potential for avalanche. Ninety percent of the people involved in an avalanche were the direct cause of the avalanche. Eighty percent of avalanches happen during or after a major snow storm. Therefore, we could assume that as many as 10 percent of avalanches are caused by either disgruntled Yetis or the elusive Sasquatch. However, this is serious; an average of 22 people die in avalanches in the United States but the vast majority of those deaths occur by people engaging in snow sports other than snowshoeing.

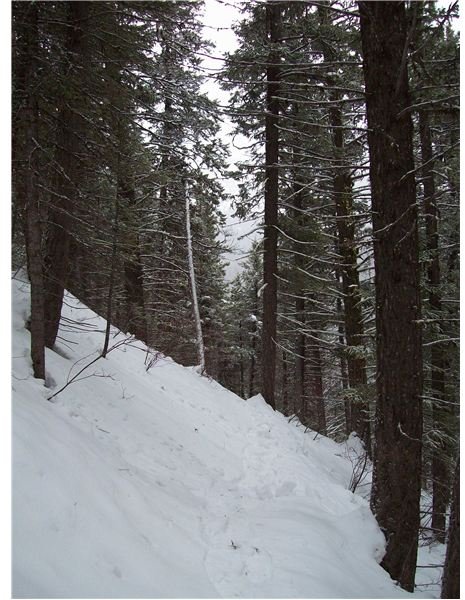

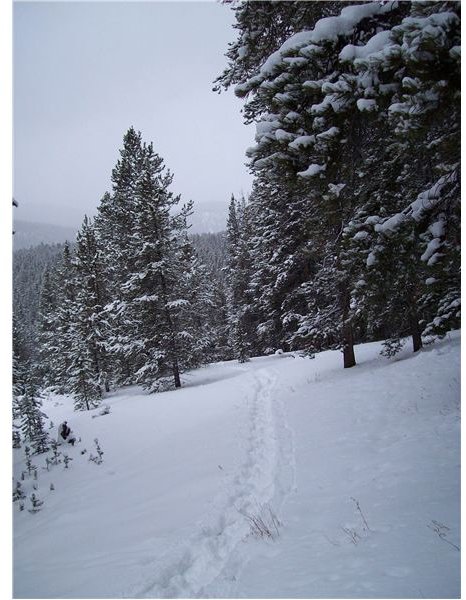

Terrain, weather, and snowpack are good predictors of avalanche conditions. Fresh snow on an already packed layer of snow is extremely dangerous. The different constitutions of snow-pack layers cause instability. Stay out of narrow ravines where there are high slopes on either side. The level of avalanche danger increases exponentially when you get above the tree line. The bottom line; if you’re planning on heading into avalanche country, take an avalanche safety course and carry the items they teach you how to use which are an avalanche beacon, shovel, and probe. They even design a coat with avalanche beacon already installed in it that you can buy now.

Cross any unavoidable slope one at a time. Remember that it’s safer to cross, climb, or descend through the trees or at the top of a wide ridge rather than somewhere in the middle. Take turns breaking trail because this is the hardest part of snowshoeing and it’s also rather unfair having the same person always on point-detail risking the most. Snow slides tend to happen in the same places so check for signs like trees and limbs ripped up and mangled, plus big clumps and heaps of snow. Avalanche chutes are relatively obvious to spot.

Cracking and eerie creaking are sights and sounds to avoid. I once experienced both, alone on a steep slope of the 10,217 foot Comet Peak in the Pioneer Mountains of South West Montana when I was young and foolish, but by crossing as quickly and cautiously from one large rock to another, I was able to make it to safety. A comet and surviving recklessness in those prime signs of slow-slide potential are rare. Check the weather report but know that things can change rapidly when you’re out there. Time and experience spent with seasoned back country experts and guides is a very good idea.

Take an Avalanche Safety Course

The best thing you can do is refer to the experts at https://www.avalanche.org/. This is an outstanding and comprehensive resource to consult before you venture out anywhere in the U.S. or Canada. This site links you to Avalanche Centers around these two countries so you can read daily bulletins about local conditions (low, moderate, and high) plus you can find out where and when avalanche safety courses will be held which include how to operate beacons and search and rescue techniques. On the home page, a convenient map marked with the location of each individual location will get you to all the information you need for that area. The various Avalanche Centers spread around the mountainous regions are hosted by the Forest Service or other government agency responsible for that particular forest. These reports don’t include privately owned ski areas which should have their own safety experts posting reports on back-country snow pack conditions.

If you haven’t taken an avalanche course and still want to head into the mountains, stay on the trails that avoid any slopes or potentially risky areas altogether. Use good judgment, avoid taking unnecessary risks, and never let the vital energy you might need to survive be burned up by senseless panicking. If you are caught in one (which is highly unlikely if you adhere to the above advice) first try to hold on to a rock or tree like your life depended on it. If you are swept away, try to swim and corkscrew in an attempt to stay on top, protect your face and mouth by sliding your neck gator over them, and dig desperately to create an air pocket immediately. As soon as the snow stops moving it will settle like concrete and the vast majority of deaths caused by this phenomenal display of nature’s fury are the result of suffocation. Keeping an eye out for the last place you saw a member of your party caught in avalanche and quickly marking it is the best chance you have at saving their life.

Sources: