Food Digestion - How Does the Digestive System Work?

Functions of the Digestive System

Digestion can be divided into 5 processes, each doing a specific job:

- Ingestion, taking in food

- Propulsion, moving food through the gastrointestinal (GI) tract

- Digestion, which includes mechanical digestion, the breakdown of food by chewing and the churning of the stomach, and chemical digestion, in which enzymes and digestive juices break down the food into molecules

- Absorption of the nutrients

- Elimination of the waste from the body.

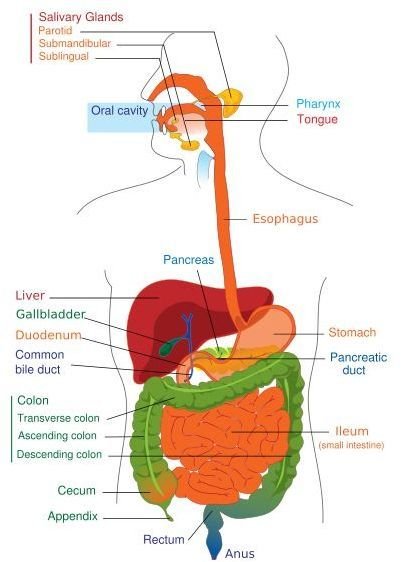

Digestion Begins in the Mouth

The digestive process starts as soon as we take a bite of food. Mastication, or chewing, mechanically breaks down food into small pieces, increasing the surface area so that saliva and other digestive juices can have greater access to the food. Saliva, produced by the salivary glands, contains an enzyme called amylase, which begins the breakdown of carbohydrates into sugar.

Once chewed, the mass of food, called a bolus, is swallowed and propelled down the esophagus by peristalsis, a squeezing action of the muscles. The lower esophageal sphincter muscle, also called the cardiac sphincter muscle, opens and the food enters the stomach.

Food is Liquefied and Acidified in the Stomach

The sight, smell, taste or even thought of food stimulates the production of gastric juice, as the stomach gets ready to do its job. Gastric juice consists of water, hormones, digestive enzymes and hydrochloric acid. When the bolus reaches the stomach, it triggers specialized cells to secrete a hormone called gastrin, which further stimulates production of gastric juice.

The bolus is liquefied by the gastric juice and the churning action of three layers of stomach muscles. The hydrochloric acid in the gastric juice lowers the pH to below 2, necessary to activate enzymes called pepsins. These enzymes begin the chemical digestion of proteins, breaking them down into polypeptides. The acid also helps to kill harmful bacteria that may have been ingested. Why doesn’t the stomach digest itself? Cells of the stomach lining secrete mucus to protect it.

Once the food in the stomach becomes liquefied, which usually takes 2-4 hours, it is known as chyme. The pyloric sphincter muscle opens and releases the chyme into the small intestine.

Digestion of Proteins, Fats and Carbohydrates in the Small Intestine

Chemical digestion of proteins, fats and carbohydrates is completed in the small intestine, aided by the action of bile and pancreatic juice. Bile, produced by the liver and stored in the gall bladder, contains bile salts, which emulsify fats. Pancreatic juice, made in the pancreas, contains bicarbonate, which is alkaline and serves to neutralize the acidic chyme. Also in the pancreatic juice are three types of digestive enzymes: proteases that break down proteins into dipeptides, tripeptides and amino acids; amylases that reduce carbohydrates to simple sugars; and lipases that convert fats into fatty acids and triglycerides. These molecules, along with other nutrients including vitamins and minerals, are then absorbed by the walls of the small intestine.

The surface area of the small intestine is greatly increased by the presence of villi, tiny finger-like projections in the intestinal walls. Nutrients are absorbed through the villi, enter the circulatory system through the capillaries and are transported throughout the body.

It takes 3 to 10 hours in the small intestine to complete digestion. Once all of the nutrients are absorbed, peristalsis moves the remaining material into the large intestine.

Absorption of Water in the Large Intestine

The material passing from the small intestine into the large intestine is still liquid, and the primary function of the large intestine is to absorb water. Beneficial bacteria living in the large intestine synthesize folic acid and vitamin K, which are essential nutrients. Once the water and remaining nutrients are absorbed, peristaltic motion passes the waste out of the body.

References

https://www.faqs.org/nutrition/Diab-Em/Digestion-and-Absorption.html

Waugh, Ann and Grant, Allison (2006). Ross and Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Wellness, 10th edition. Edinburgh: Elsevier.

Image credit: Mariana Ruiz, Wikimedia Commons.