Neurobiology of PTSD: Changes In the Brain and Neurendocrine System

The Ravaging Effects of PTSD on the Human Body

Breaking down the neurobiology of PTSD enables us to see the profound changes that this sometimes dramatically disabling disorder causes in the sufferer’s mind and body. Although healing and recovery can indeed take place with the right medications, PTSD support groups, and/or medicine, a person with PTSD will never be the same after experiencing the traumatic events that caused their disorder. Their psyche is permanently changed (rewired, neurologically speaking), because the events they witnessed left indelible imprints in their brains.

Since the central nervous system is responsible for many things, including the ability to relax the body and mind, we can already guess how the hypervigilance inherent in many with PTSD may be a result of the nervous system no longer functioning as effectively as possible.

Neurobiology refers to the study of the anatomy, physiology, and biology of the nervous system from the large view of how it all should work together cohesively, right down to the tiniest chemical and cellular level where neuroendocrine receptors located in the membranes of those cells respond to stimuli. As we will soon see, the neurobiology of PTSD has been well researched to reveal and suggest that profound and maladaptive changes take place as a result of that stress which creates the ongoing symptoms and common behaviors of people with PTSD.

Studies Regarding Neurobiological Consequences of PTSD in Children

First off, it has been found that children with PTSD symptoms have alterations in the chemical mediators of stress within their neuroendocrine system as well as an abnormal, adverse development in the prefrontal region of the brain which is responsible for cognitive development (De Bellis, 2001). That can lead to an increased risk of developing mental illnesses and either developmental delays or deficits in cognitive, behavioral, emotional, and social skills. Also, if the traumatic events were very severe and witnessed at a very young age, brain volume is actually smaller too. (De Bellis, Keshavan, Baum, et al., 1999).

Major fallout from PTSD in children can include alterations in the workings of biological stress response systems from the initial stress. A heavy and disruptive impression is felt by both the neurotransmitter and neuroendocrine systems which is thought to be a contributing factor to PTSD symptoms because the biological stress systems have been dysregulated. (De Bellis, 2001). Taking it down another level, the development of enhanced stress responsiveness in a child with PTSD is likely the result of elevated cortisol and catecholamine chemicals which can also negatively impact brain development (De Bellis, 2001).

Let’s not forget that the five senses are intimately connected with the traumatic experience resulting in the onset of PTSD, and they’re all firmly intertwined with neurobiology. Thus, hyperarousal, anxiety, and the hypervigilance are also all results of this enhanced stress response in the neuroendocrine system.

The Neurobiology of PTSD In Adults

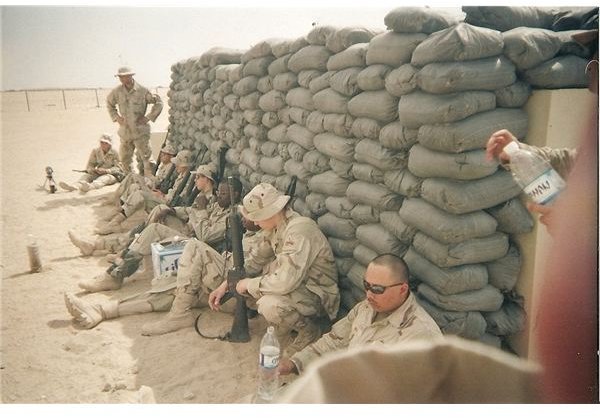

Overactive stress hormones can be the root of many of the problematic and abnormal behaviors associated with PTSD. As a combat veteran with PTSD, I can attest to the fact that once anger triggers that release of cortisol (remember from the De Bellis, 2001 study above that there are elevated levels associated with PTSD), it takes an exceedingly long time (sometimes days) to return to a normal level of homeostasis. Often there is a crash after those extreme emotions dissipate as if the body and mind is totally spent. Activities like yoga, meditation, and the non-combative martial arts have been very helpful in soothing and perhaps even restoring my impaired central nervous system to pre-war status.

Brain volume changes are also found in PTSD adults, specifically reduced hippocampal volume (Bremmer et al., 1995). Since the hippocampus is involved in memory, it may play a part in some of the symptoms of the disorder.

Intrusive thoughts and the inability to forget are inherent with PTSD. However, to date, the exact ramifications of this affected area of the brain aren’t clear. All this research aside, it’s vital to note that everything someone with PTSD can do to rewire their brain positively should be done. There is much plasticity in the brain; it can be changed for the better.

As future studies linking more conclusively the role of altered neuroendocrine system components in all types of PTSD, we get a clearer picture of all that PTSD does to the body and brain. Since studies of combat veterans with PTSD, children, rape victims, and any of the other causes of this trauma-related disorder are inherently different to some extent, a lot of work lies ahead before the researchers are entirely sure about all the multifaceted implications of their findings.

These are incredibly complex systems in our bodies, and there are virtually an infinite number of variables, but we can applaud the good work that has been done thus far. All of it can move us a few steps forward in finding the best best PTSD treatments and medications to alleviate the burdens that many with this life-disrupting disorder carry.

Image courtesy of the author

References

De Bellis, M.D. (2001). Development traumatology: The psychobiological development of maltreated children and its implications for research, treatment, and policy. Development and Psychopathology, 13, 537 - 561.

De Bellis MD, Keshavan MS, Clark DB, Casey BJ, Giedd J, Boring AM, Frustaci K, Ryan ND: AE Bennett Research Award. Developmental traumatology. Part II: Brain development. Biological Psychiatry, 1999; 45:1271–1284

Bremner JD, Randall P, Vermetten E, Staib L, Bronen RA, Capelli S, Mazure CM, McCarthy G, Charney DS, Innis RB: MRI-based measurement of hippocampal volume in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 1995; 152:973–981.